The Jewish Contribution to the Development of Olomouc, 1848-1938

The modern history of the Jewish community in Olomouc lasted less than a century, and spanned the fortunes of just three or four generations, whose memory today largely survives only in the gravestones of the Jewish part of the central cemetery, or in the factory buildings of the companies they founded. For its beginnings we must look to the year of revolutionary ferment, 1848-9, which saw an end to the medieval ghettos and heralded fundamental change to the legal status of Jews within the Austro-Hungarian empire. Formerly prohibited from residing in the then royal capital city of Olomouc, they were at last granted freedom to move and to settle wherever they desired, the first Jewish family to move in being that of Leopold Hamburger, corn merchant from nearby Prostějov. Within two decades, Jews were granted further civil rights. In 1860 they were allowed to acquire real estate in Olomouc, and in 1867, with the enactment of the December Constitution, they were given equal rights with other citizens, including the right to register their domicile in the city.

Unlike other Moravian towns and cities, Olomouc was physically restricted in its capacity for expansion by the existence of the old imperial fortifications, which were protected by law until 1887 under the so-called Demolition Reverse Act. Nevertheless it enjoyed growing importance as the political and administrative centre of a highly developed agricultural region with several important markets, and in 1873 its status as a major transport junction was also reinforced with the growth of the rail network.

Meanwhile, Jewish families continued to move in, above all from the neighboring towns of Prostějov, Lipník, Úsov, Loštic and Přerov, but also from farther afield. By the early 1850s Olomouc already had a sizeable Jewish community, and in 1857 this numbered 238 people, or 1.75% of the entire population. And the growth continued until 1900, when 1,676 persons of the Jewish faith were recorded as living in the city, i.e. 7.7% of all its citizens.

The greatest concentrations of Jewish population were in the urban districts of Nová Ulice, Hodolany and Pavlovičky; interestingly, no Jewish inhabitants were recorded for Povel and Řepčín between 1800 and 1900.

From the 1850s onwards, it was Jewish merchants above all who were to inject a new entrepreneurial spirit into the city. Their strengthening role in its economic life is reflected in the records showing who held the leases for various enterprises and properties owned by the municipality. From 1858, for example, the city brewery was licensed to Singer & Hamburger, the municipal distilleries were leased by the Fleischmann family from Úsov, and from 1867 the May brothers had acquired municipal landholdings at Horka, Skrbeň and Unčovice.

In the 1860s we find Jewish merchants and traders dealing with fancy goods and manufactured wares, grain, wine, coal and rags, a number of Jewish firms were engaged in the production and sale of spirit, liqueurs and vinegar, and also in freight forwarding and factoring.

Businesses and entrepreneurs listed in 1864 include the printer and publisher Josef Groák, while in 1870 one of the city’s most important photographic studios was founded by Sigmund Wasservogel from Úsov. In this case the firm’s expansion was typical, with numerous members of the family helping to set up further companies in six other Moravian towns.

The rising numbers and economic influence of the Jewish population from the 1860s was also accompanied by their growing role in political and public life.

With few exceptions, however, this amounted to a strengthening of German public life. German was, after all, the language which had been adopted by the Jews, and Joseph II’s decrees of a century earlier, and the imposition of compulsory schooling in the German language, had helped lead to the Germanisation of Jews in Moravia. For this reason the Jews of Olomouc were supportive of the interests of the German-speaking authorities in the city and were active in German cultural associations and school institutions.

A leading representative of Jewish-German liberalism was the advocate and journalist Dr Jakob Eben (1842-1919), political affairs adviser to the mayor Josef Engel (1872-1896). In 1872 Eben established the weekly Das deutsche Volksblatt für Mähren, known from 1880 as the Mährisches Tagblatt. This newspaper became the official paper of the Olomouc City Hall.

The Jewish community had its own recognized representatives in the municipal authority from 1884, with the election of maltster Eduard Hamburger, who remained a Councillor till his death in 1901. Other leading members of the Jewish community followed: in 1898 the liqueur manufacturer Josef Loew, in 1902-5 the advocate Dr Jakob Eben, in 1908-18 the corn merchant Jonas Fischer, in 1910-3 the leather merchant Max Deutsch. Further testament to the growing influence of Jews in public life is the active role played as City Council alderman in 1908-18 by Friedrich Fischel, malt-house proprietor at Olomouc-Bělidla.

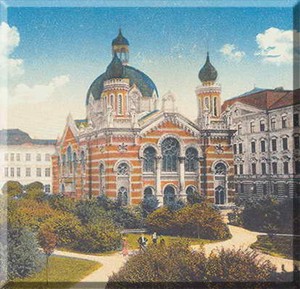

Up to the 1890s, purely Jewish organisations tended to restrict themselves to satisfying the religious needs of the community and supporting the charitable institutions which had always been typical of Jewish society. A Chevra Kadisha burial society was probably already active in Olomouc by 1861, well before the founding of the first Jewish Religious Association in 1865. The first chairman of the Association was the merchant Herrmann Zweig, and another co-founder was the major figure of Adolf Brecher M.D., who was renowned among other things as a lyrical poet and translator of Vrchlický into the German language. In 1867 the Association established a new prayer room and also a cemetery, and its growing importance in Moravia as a whole was confirmed in 1891 with the decision that it should become an independent Jewish Religious Community. The golden years of this Community were to witness the construction of the magnificent new synagogue. They were also to see a massive increase in the number of charitable foundations and scholarships for those in need, regardless of their religious denomination – such as Dr Adolf Brecher’s Scholarship Fund for young students.

Already in 1897, local adherents of Herzl’s Zionist movement, though few in number, were founding new associations in Olomouc which subscribed to the idea of a Jewish national identity. Under the leadership of Wilhelm Spitzer, the Zionist association Sion was established, and so also was the Zionist academic holiday association, Geullah. Of great importance was the setting up of a Jewish library, and also a literary society which organized public lectures until 1914. No less significant was the Jewish physical training and sports association, which was reorganized in 1927 under the title Makkabi.

New legislation in 1920 meant that at the time of the census, people were able to state their ethnic origin, rather than their language of custom, as their nationality. During the 1921 census, largely as a result of the Zionist movement, 38.1% of Jews in Olomouc cited their nationality as Jewish. The Jews of Olomouc always had at least one representative in the municipal authority throughout the First Czechoslovak Republic, most notably Rudolf Schulhof, who was active within it from 1932. But the following year brought a watershed in the community’s tendency away from a German identity, with the spread of the Czech-Jewish movement from Bohemia to Moravia.

The Jewish contribution to the prosperity of Olomouc was rooted primarily in Jewish industrial acumen, and it is largely to the credit of the Jewish business men of earlier times that the city owes its modern industrial structure. It was Jewish business which accumulated the finance needed to set up manufacturing companies in the 1870s in the suburbs of those days. And from 1876, when the first inner city ramparts of the once glorious Olomouc fortress were demolished, it was Jewish entrepreneurs too who took part in developing what until then had been a city rigidly constrained by its own walls. Among the most successful developers was Moritz Fischer, who by 1902 built over 60 apartment houses on newly-cleared land which had formerly been part of the city fortifications. It was he who built the new maltings at Holice in 1899, and before his company was wound up in 1903 he was also the lessee of the municipal brickworks at Bystrovany.

Up to the fateful year 1939, which first meant the exclusion of Jews from public life and in the next phase brought the confiscation of all their assets and the physical liquidation of members of the Jewish community by the Nazis, Jews were the traditional suppliers of corn, flour, spirits, textiles, hides and leather, scrap iron, foodstuffs and exotic fruit, and most of the city’s shopkeepers and traders were Jewish.

Jewish capital was essential in establishing the city’s key food industry sectors, especially malt production, sugar refining, and the production of yeast, vinegar, confectionery and preserves.

The first of the big food industry concerns was that of the brothers A. & H. May at Olomouc-Hejčín, founded in 1851 and comprising first a distillery and yeast factory, then from 1862 also a sugar works and refinery.

Jewish companies were decisive in ensuring the city’s pre-eminence in the production of malt, which developed into one of the most advanced sectors of the local foodstuffs industry. The biggest malt producing companies included Herrmann Brach, established at Bělidla in 1872, Ignaz & Wilhelm Briess, established at Pavlovičky in 1873, Markus Zweig & Sons, established at Lazce in 1876, Eduard Hamburger, established at Nová Ulice in 1884, and also Heller & Husserl, which took over the malt-house at Holice in 1907.

During the 1930s Saul Heikorn’s factory (today the MILO works) rose to major significance in the production of edible fats, vegetable oils, soap, vinegar and other products, while Hugo König’s fish cannery was of considerable importance in the development of the canning industry as a whole. A big name in the sweets and chocolate industry was that of Filip Deutsch, who manufactured confectionery from 1877 and whose descendants built a new factory near the municipal abattoir in 1914. Other big food companies included the Singer & Hamburger yeast works and distillery at Pavlovičky; the Fleischmann family’s vinegar factory in the same district, later owned by Donath, and also the Leopold Fromowitz steam flour mill at Chválkovice. Quite a few Jewish firms were also involved in the textile industry, a major manufacturer of delicate fashion fabrics being Engelmann & Co.

Many leading personalities in the Olomouc Jewish community were eminent also in the professions and the arts. Of these the greatest impressions on the history of the city were made perhaps by the X-ray pioneer Dr Rudolf Bacher, and also the architects Jacques Groag and Paul Engelmann, whose modern apartment blocks are to be admired in Olomouc to the present day.